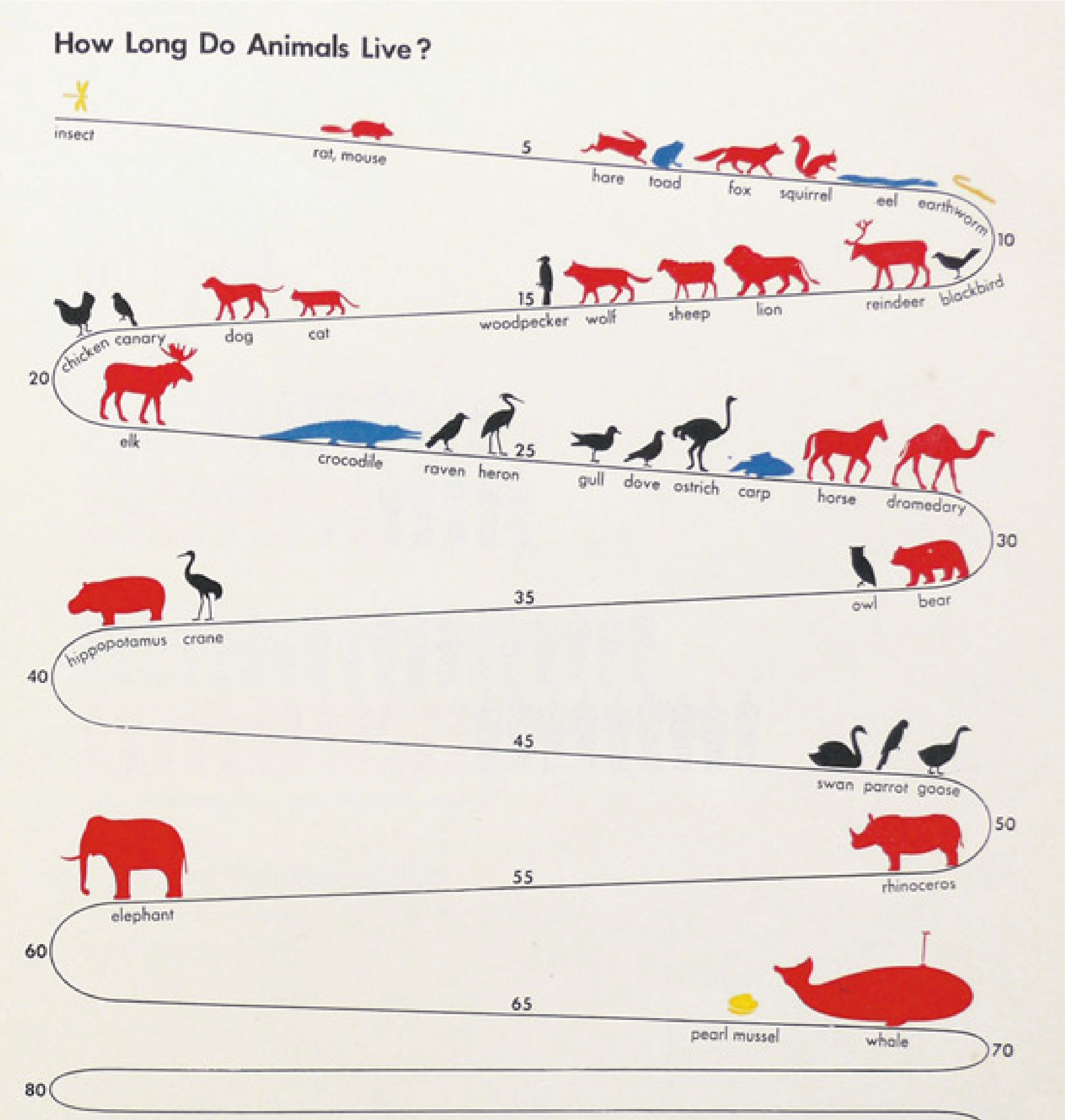

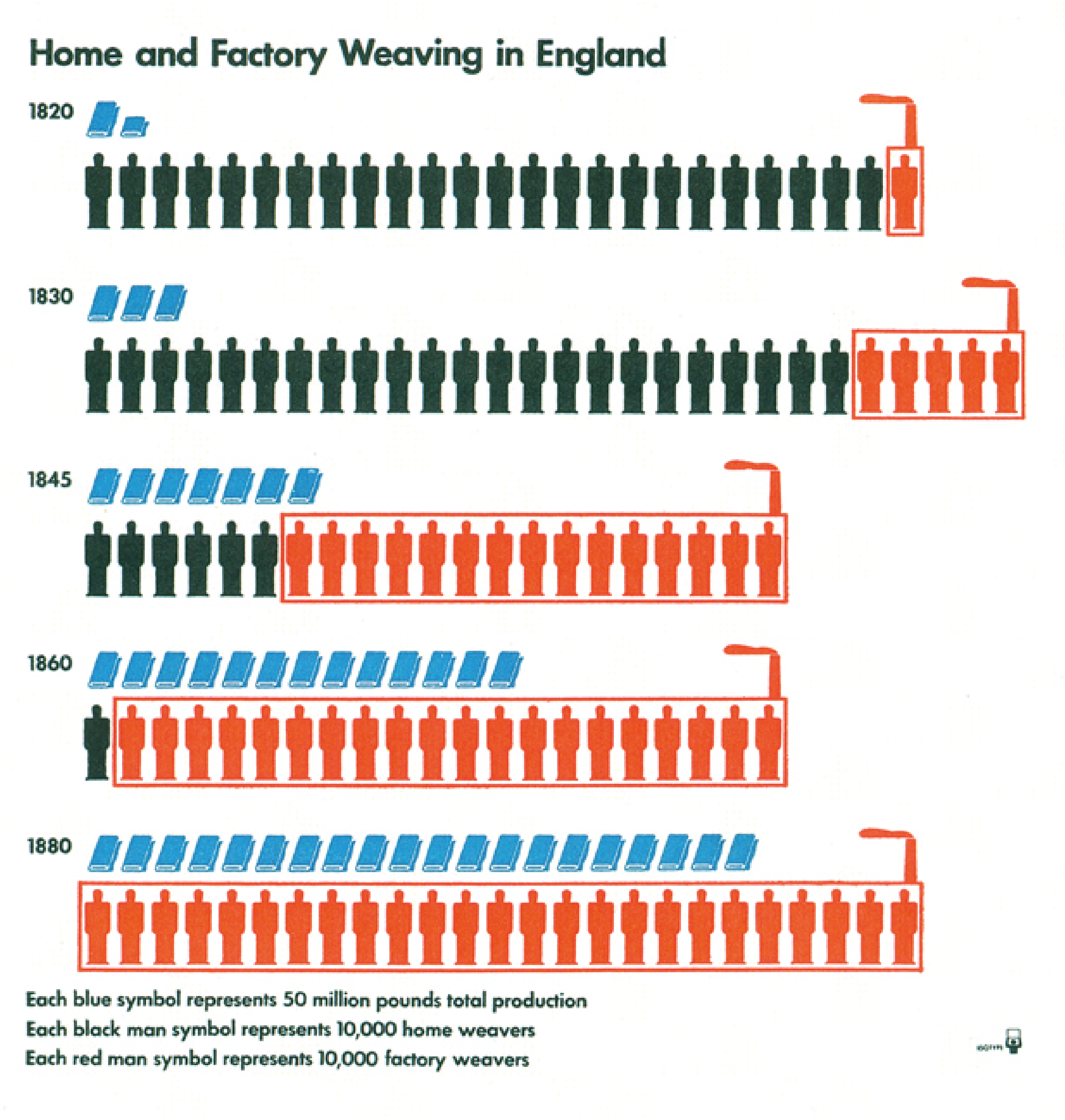

Graphics created by the isotype movement, featured in The Transformer by Marie Neurath and Robin Kinross

It continues today, with David McCandless taking a treemap, ignoring its hierarchical structure, and creating his billion-dollar-a-gram or Valentina D’Efilippo turning a multi-dimensional scatter chart into a poppy field to commemorate the millions who have lost their lives in warfare. Journalists at the Guardian, New York Times, Reuters, South China Morning Post and elsewhere have created new kinds of visual storytelling to reflect new technology and the changing needs of their audience - most recently, by figuring out how charting and mapping needs to adapt to work on mobile screens.

Of course, these designers draw on conventions and traditions. Each chart is still recognisable as a chart; it is not a virgin birth, divorced from the past; otherwise, readers would not know what they were looking at. But this balance between convention and novelty, tradition and originality is clearly detectable whenever a data story is successful: not too conventional (which is boring), and not too original (which is confusing), but somewhere in between, so that an audience is both reassured (I understand this) and challenged (I’ve never thought about it like that!). If you’re particularly skilled, your audience will reach a state of ‘moderate transient stress’ or immersion - to quote Robert Sapolsky - which is where we are all happiest.

Which brings us back to where we started. Since a fresh perspective is often a key part of data visualisation, it is hard to prescribe rules, because rules can limit innovation. Furthermore, what is innovative for one audience is distracting for another, so even if you could define rules on where and how to innovate, they would be too context-dependent to be useful. Instead, the best approach is to be aware of good models and general design principles, but to always be mindful of where your story needs to break the rules or break new ground to be emotionally effective.

So are we right? That’s what we want to test in the coming months. We’re going to sense check every data viz rule we can find and see if it holds up under pressure. Our hypothesis is that even the most sensible-sounding rule (‘Don’t use Comic Sans’, ‘Never use a marimekko chart’) has important exceptions. When the task is to communicate with an audience, the ‘wrong answer’ might be exactly what’s required to surprise or intrigue them.

We’d love your help with this. Are there data viz rules that you think should always be slavishly adhered to - no matter what? Get in touch or contact us on social media, and we’ll add it to the list. Or perhaps there are rules that you think are absurd. We’ll try to show that, in some cases, they aren’t.

At the very least, we should end up with a useful catalogue of received wisdom. After all, it doesn’t hurt to know what the conventions are, even if you end up working more instinctively. It’s hard to innovate unless you know what’s already been tried.

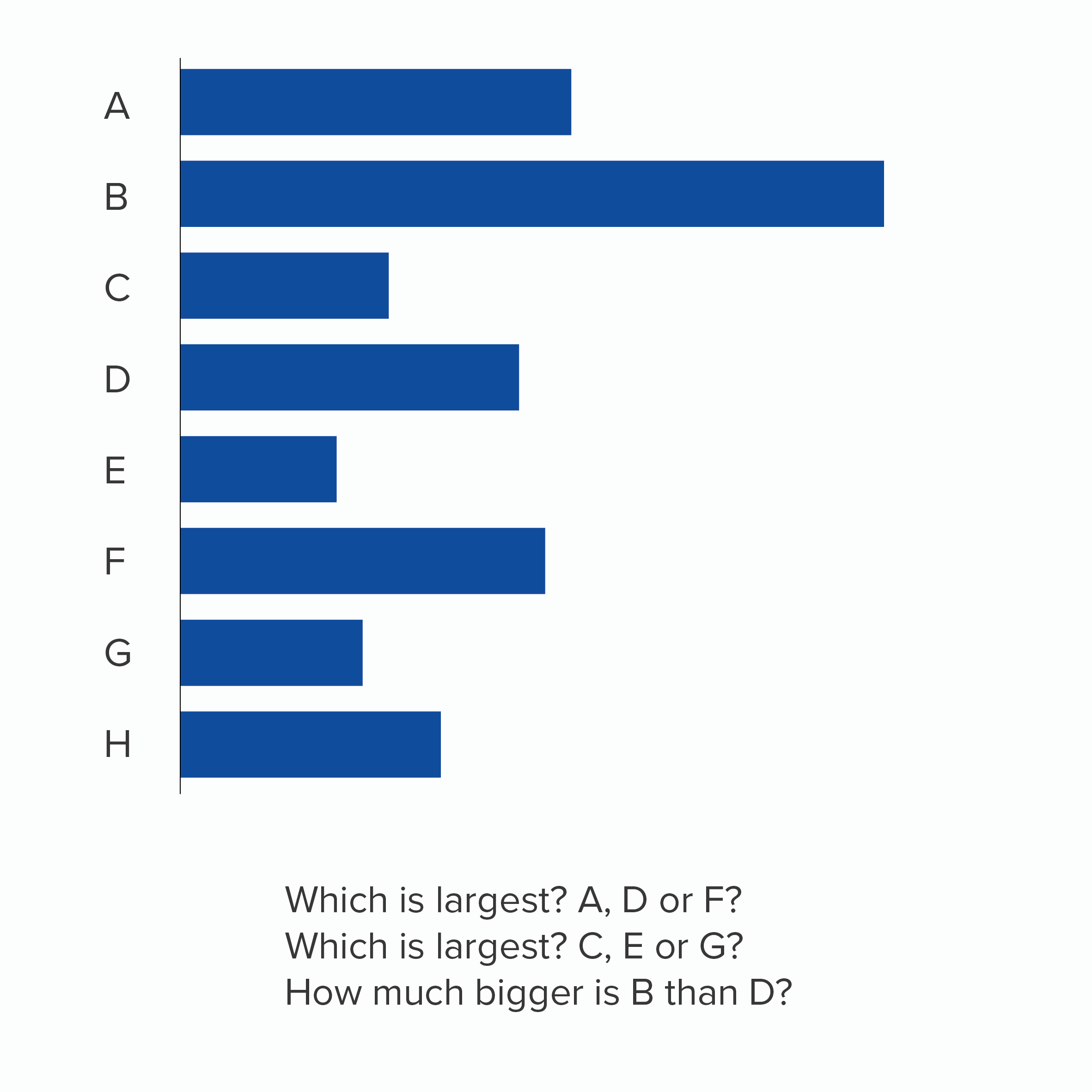

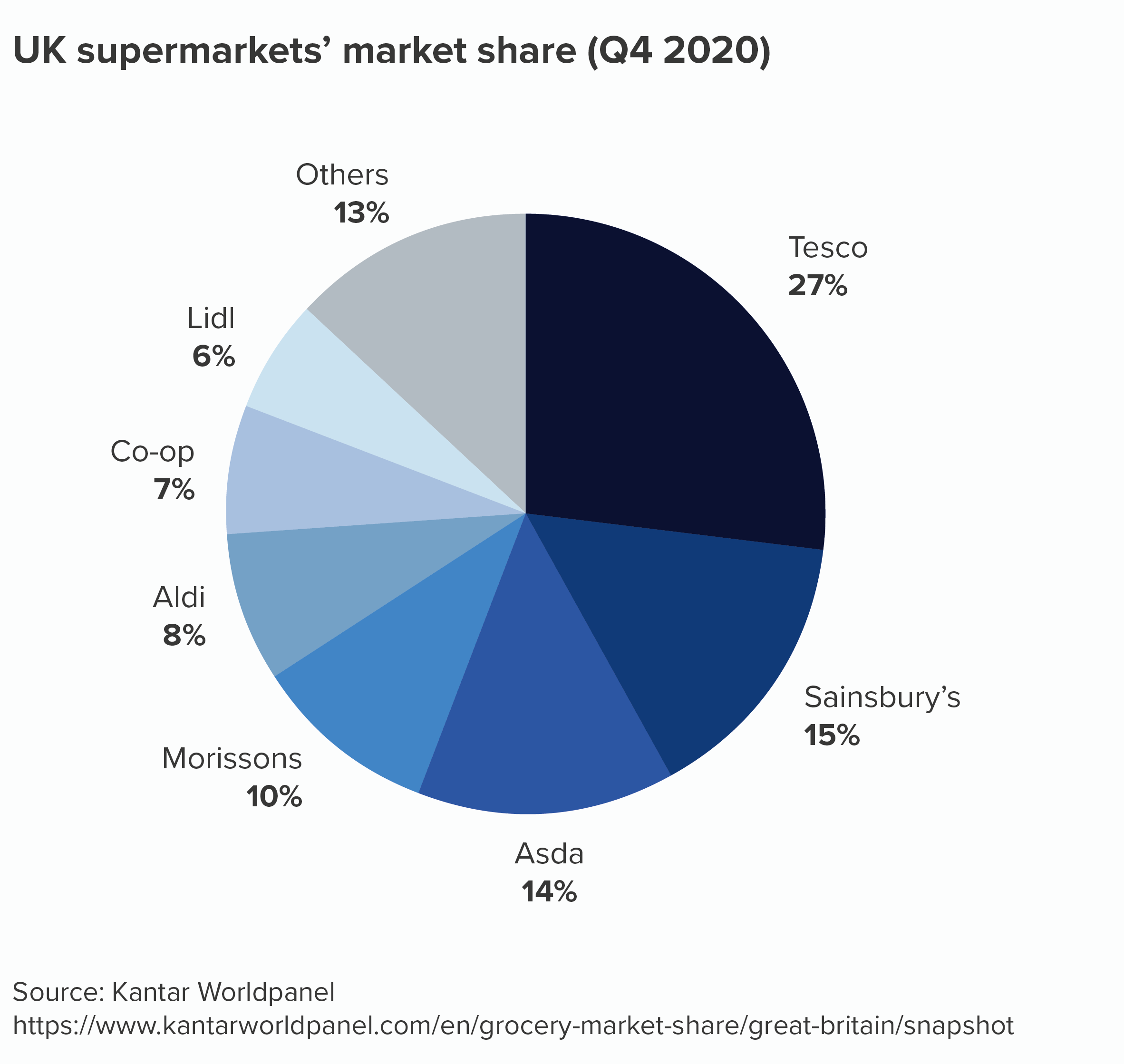

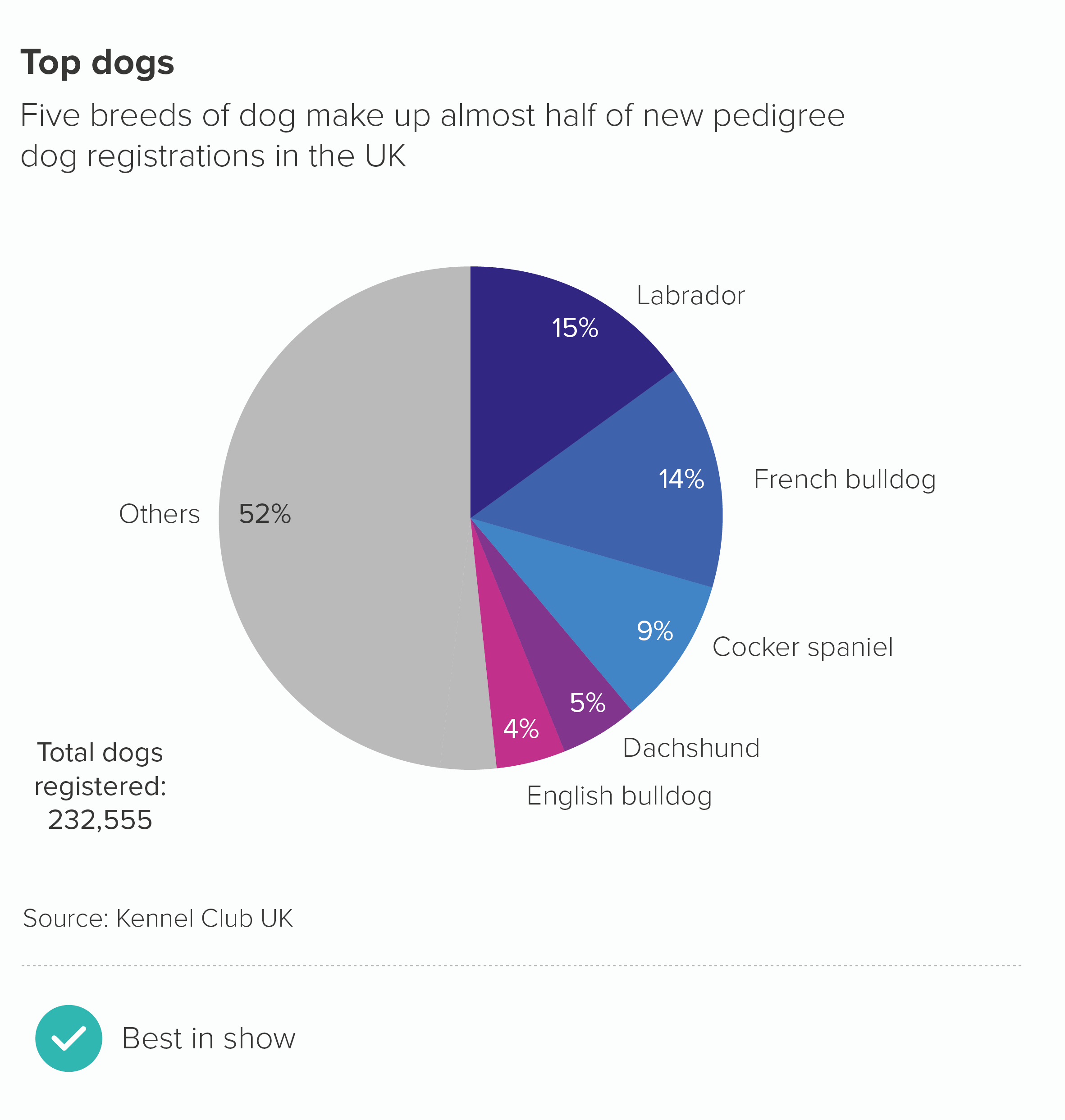

We’ll kick off with the most rule-bound chart category of all: the pie chart. It turns out that people have extremely strong opinions about the humble pie, including its right to even exist. Which is less of a rule and more a dictatorial edict. Let’s see if we can’t stage a rescue mission and show that the pie chart is not just worth saving, but celebrating.

All the rules so far - on one big shiny page

Individual rules:

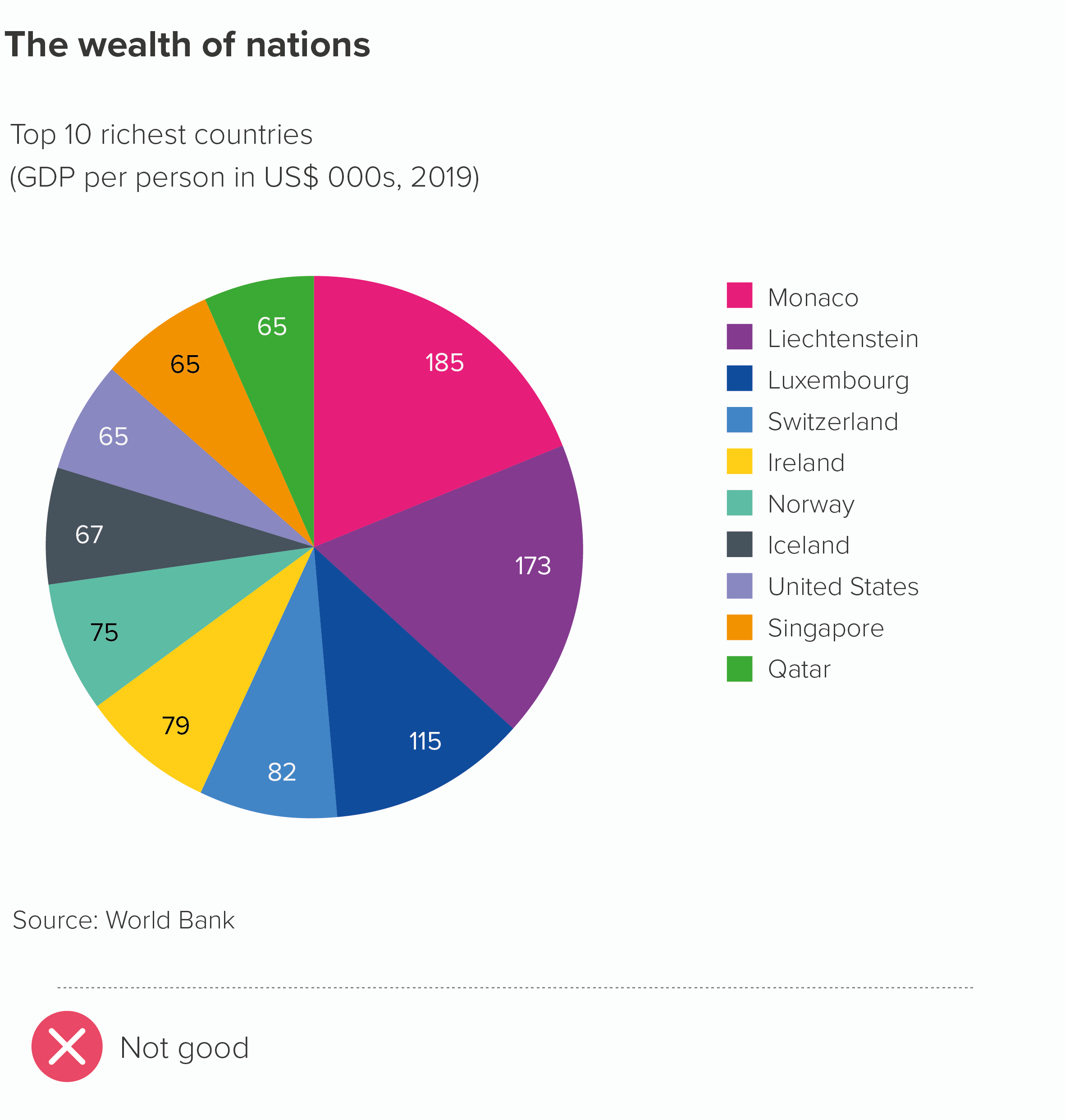

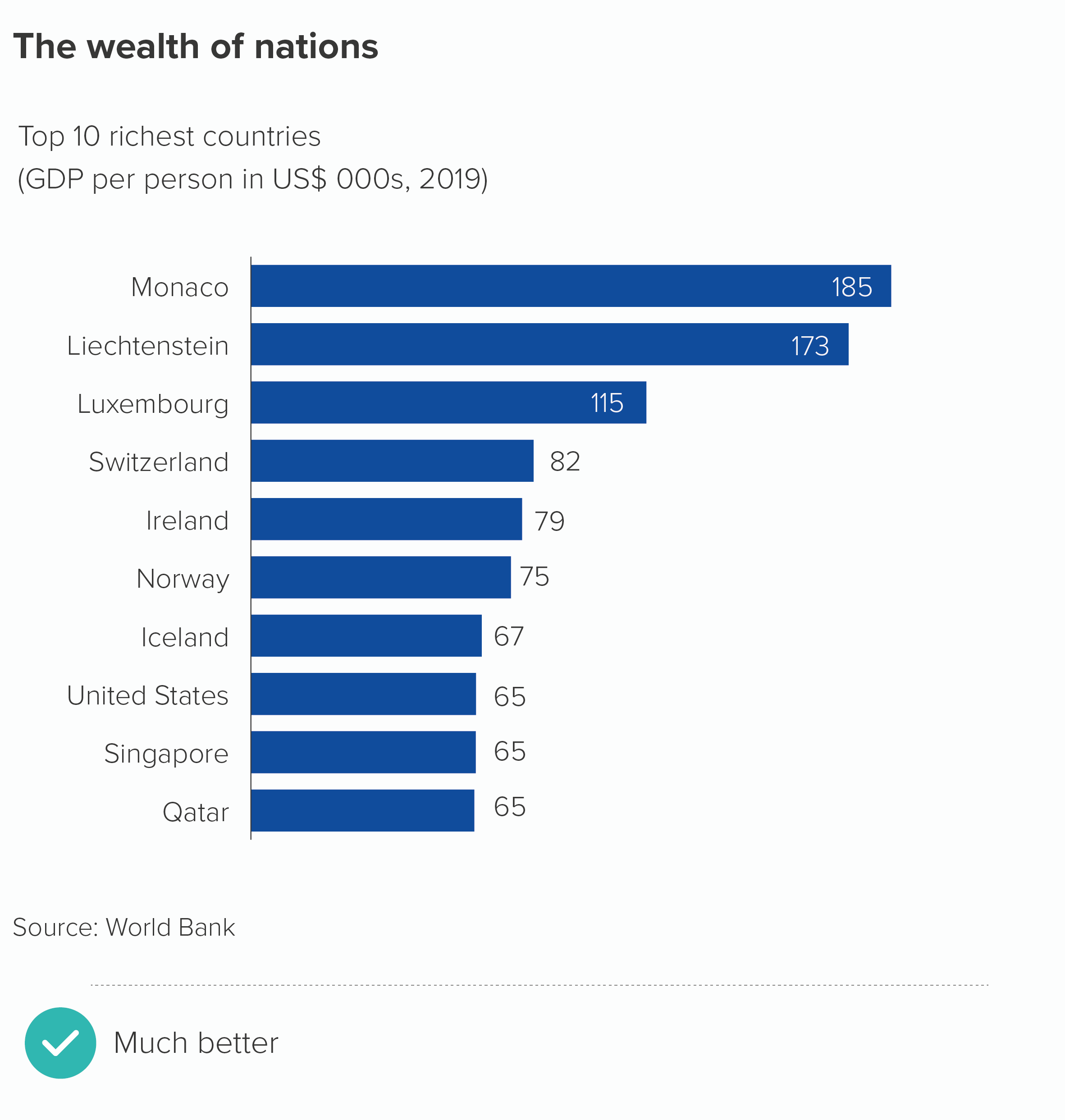

Rule 1: Pie charts should never be used

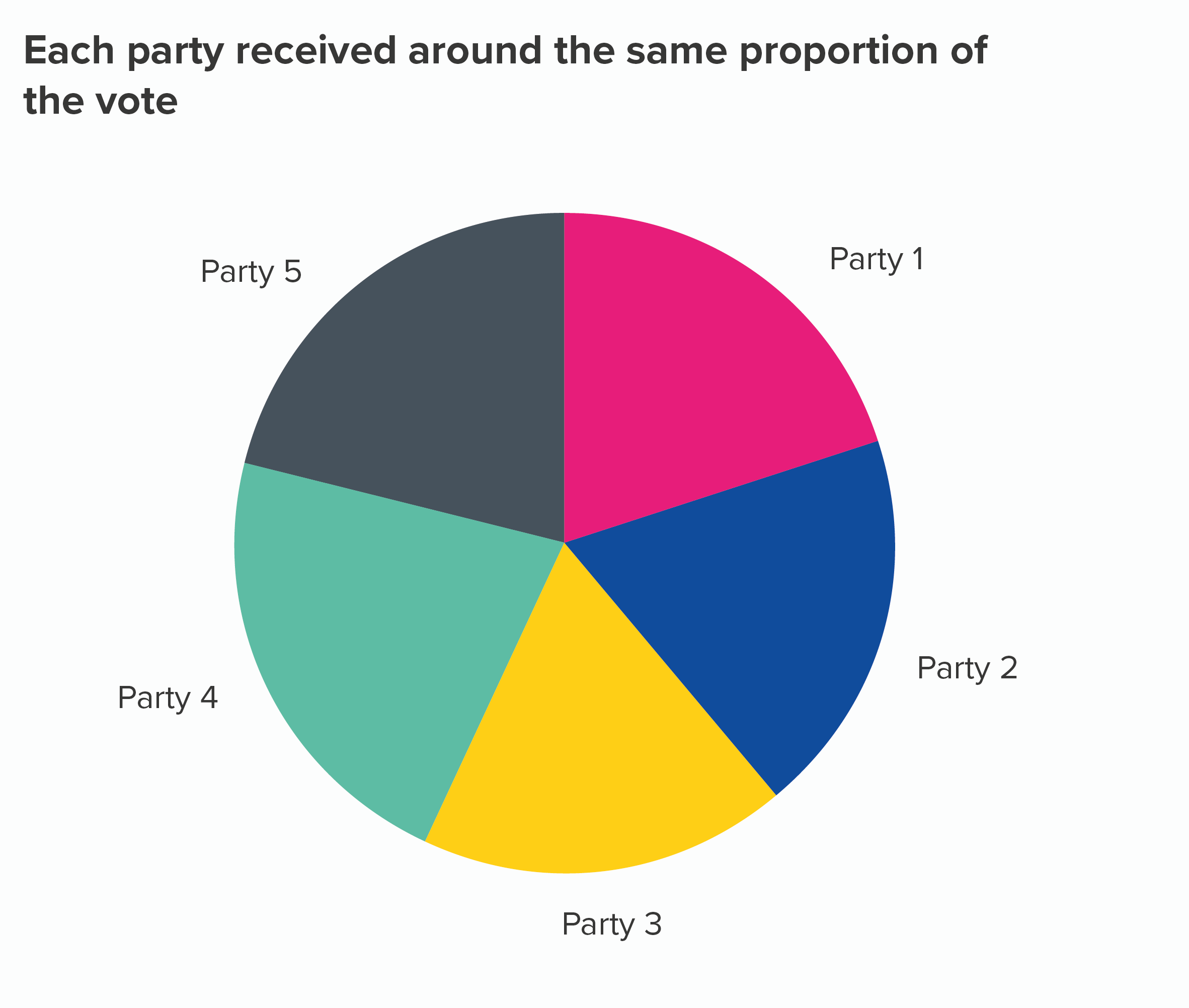

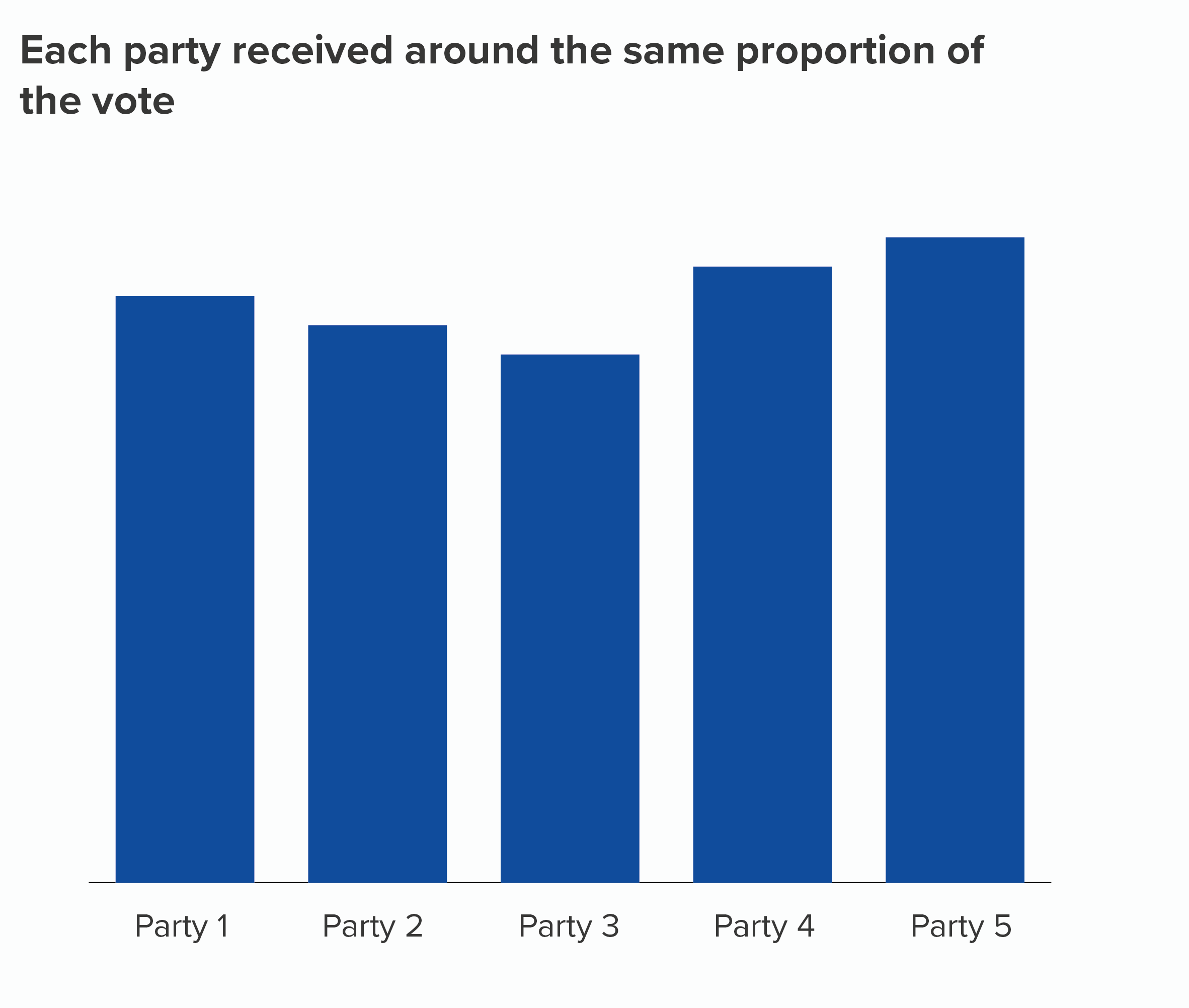

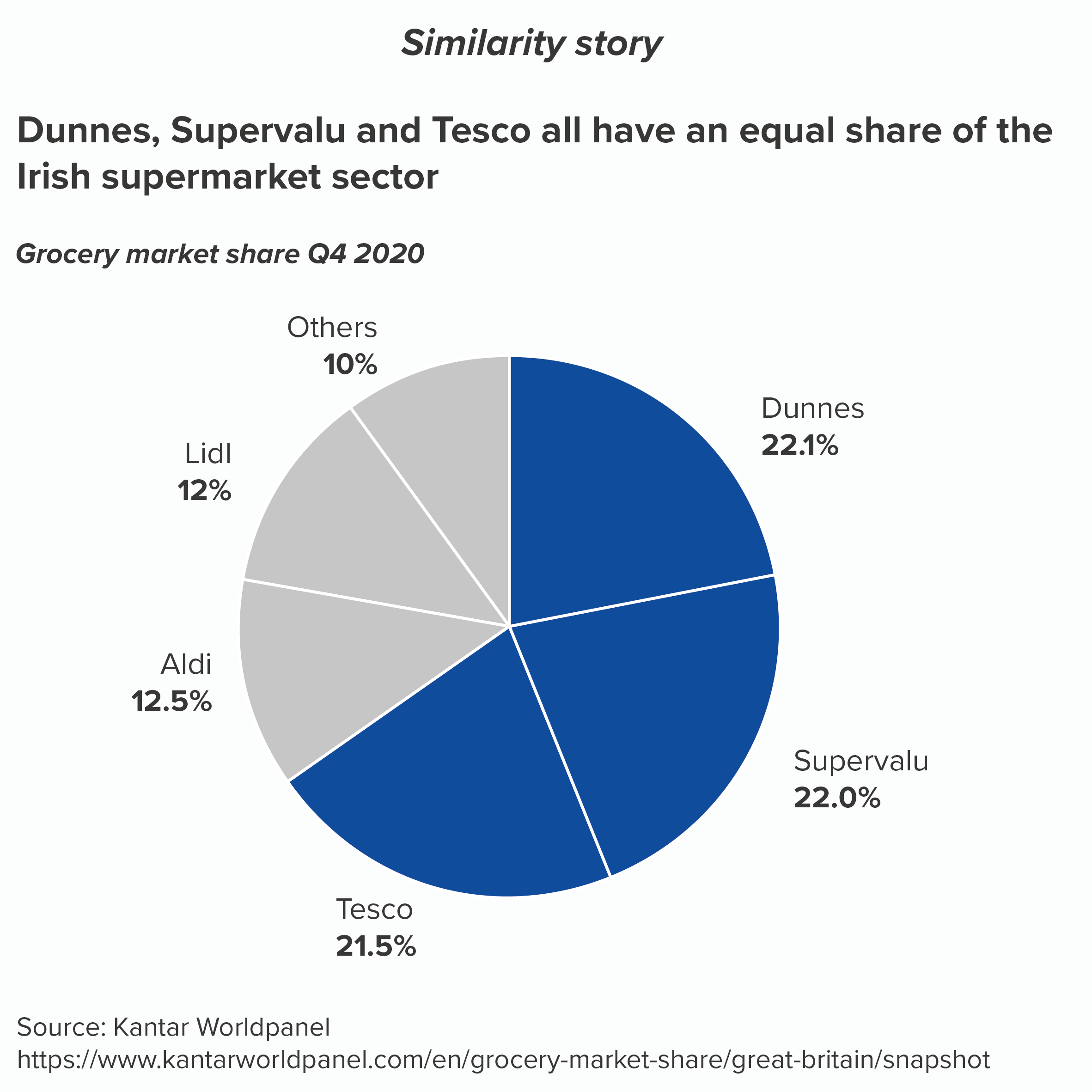

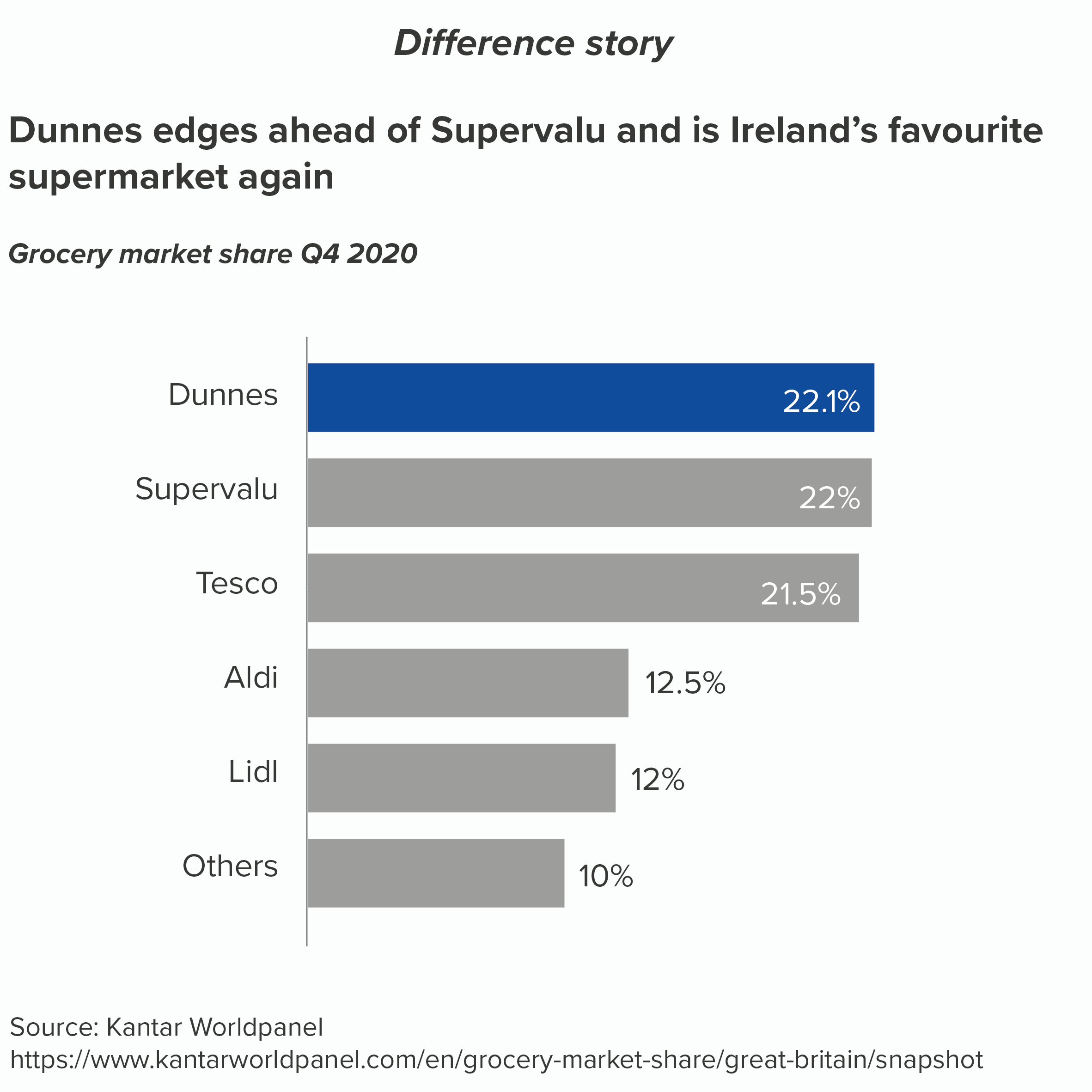

Rule 2: Avoid pies when your values are similar

Rule 3: Not too many pie slices, not too few

Rule 4: A pie chart should add up to 100%

Rule 5: Start a pie chart at 12 o’clock and go clockwise

Rule 6: Arrange your pie slices from largest to smallest

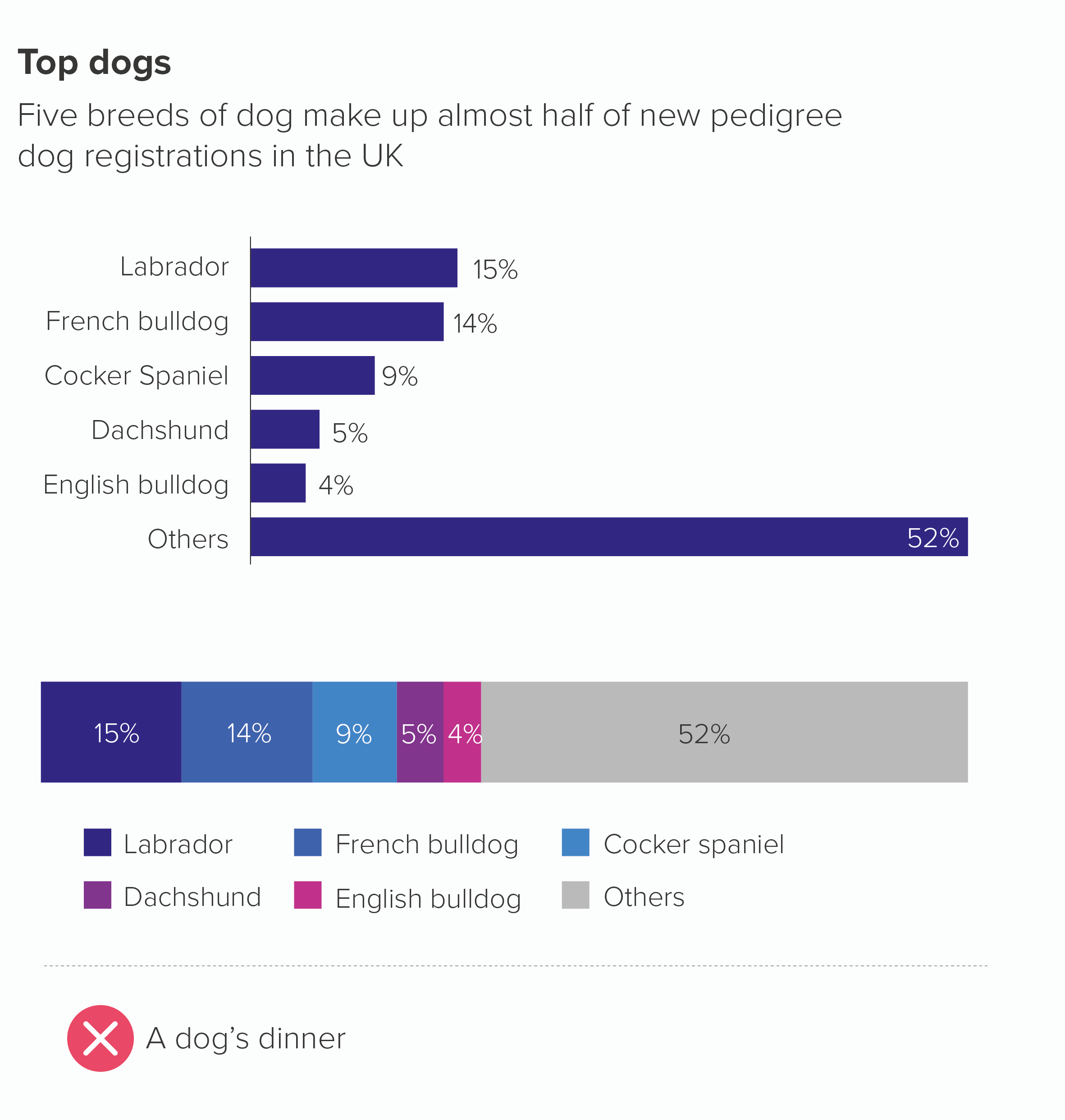

Rule 7: No exploding pies

Rule 8: Limit the number of colours in your pie chart

Rule 9: Give your pie chart a key (or legend)

Rule 10: No multiple pies

Rule 11: Don’t chain or nest pies

Rule 12: No 3D pies

Rule 13: Don’t decorate pies

Rule 14: No proportionately-sized pies

Rule 15: Don’t use doughnut charts

Rules 1-15: Pie charts - a visual summary

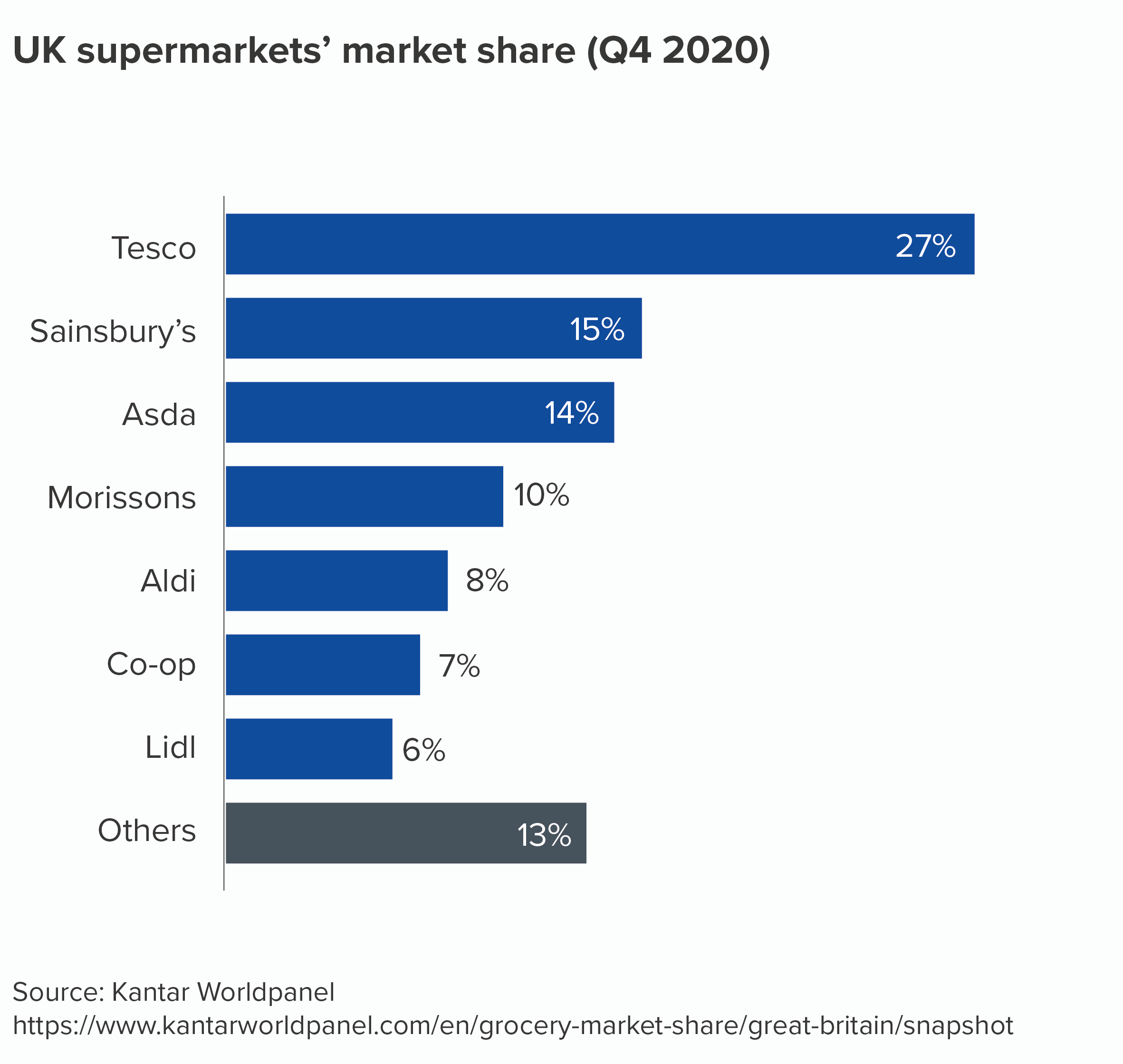

Rule 16: If in doubt, use a bar chart

Rule 17: Not too many bars

Rule 18: No multi-coloured bars

Rule 19: Arrange your bars largest to smallest

Rule 20: Keep a sensible gap between the bars

Rule 21: Bar charts need a key

Rule 22: No rounded, pointed or decorated bars

Rule 23: No 3D bars

Rule 24: Label your bars and axes

Rule 25: Always start your bar charts at zero

Rule 26: Don’t use broken axes and bars

Rule 27: No unnecessary lines on bar charts

Rules 16-27: Bar charts - a visual summary

Rule 28: Use a clustered column to show multiple series

Rule 29: ‘Use log scales for many kinds of variables’

Rule 30: A line chart should only show change over time

Rule 31: Line charts shouldn’t have too many lines

Rule 32: Every line should be a different colour

Rule 33: Each line should contain as much data as possible

Rule 34: A line chart y-axis should start at zero

Rule 35: All data markers to your lines

Rule 36: Lines should not be too thin or too thick

Rule 37: Line charts should have a key

Rule 38: No unnecessary lines on line charts

Rule 39: Label all the datapoints on your x-axis

Rule 40: No 3D line charts

Rule 41: Avoid area charts?

More data viz advice and best practice examples in our book- Communicating with Data Visualisation: A Practical Guide